Local News

Mentorship and undergraduate research help an RIT student build real-world skills and confidence for the challenges of medical school

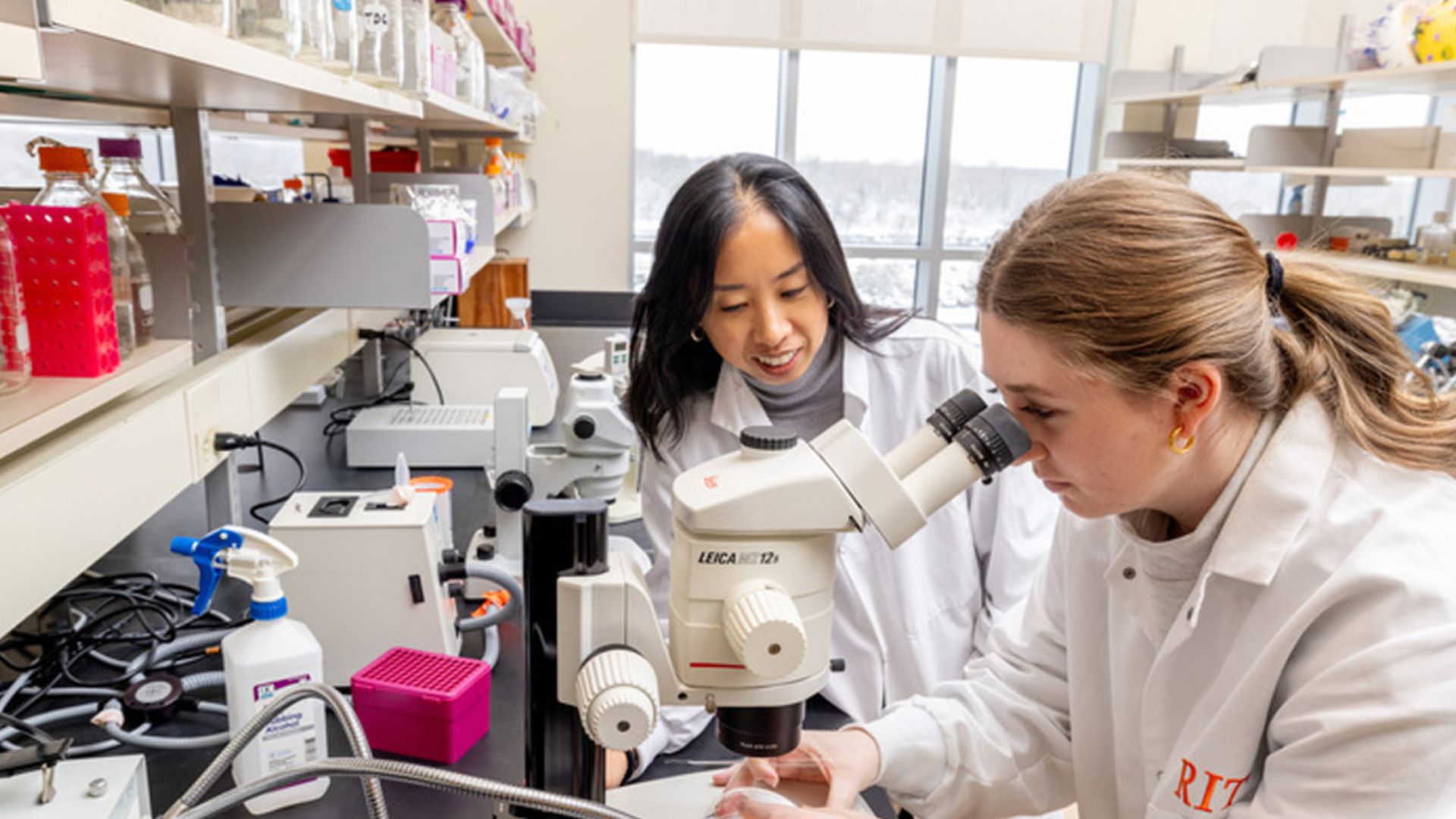

Rochester, New York – Inside a biomedical sciences lab at Rochester Institute of Technology, learning does not stop at lectures or exams. It continues at the lab bench, in careful observations, trial-and-error experiments, and conversations between a student and her mentor. For Rachel Smith, a second-year biomedical sciences major on a pre-med track, that environment has become a critical part of her preparation for medical school.

Smith, an honors student from LeRoy, N.Y., knew early on that she wanted more than classroom knowledge. Medical school demands deep understanding, discipline, and the ability to think critically under pressure. To prepare herself, she decided to pursue hands-on research as an undergraduate – an experience that would challenge her and expose her to the realities of scientific work.

Rather than waiting for an opportunity to come her way, Smith took initiative. She sent a cold email to Janet Lighthouse, an assistant professor in RIT’s biomedical sciences department, asking about potential research opportunities. That single message led to an invitation to join Lighthouse’s lab and marked the beginning of a mentorship that continues to shape Smith’s academic path.

From the start, Smith was immersed in the scientific process. She began learning laboratory techniques and core research concepts, gradually taking on more responsibility as her skills grew. Working in the lab allowed her to see how science unfolds in real time—how questions lead to experiments, how results are analyzed, and how setbacks become part of the learning process.

“When I started, I learned basic molecular procedures and scientific topics,” said Smith, who is from LeRoy, N.Y. “I didn’t think I would be running these experiments and analyzing changes in gene expression. I’m able to tell what’s happening and if it’s successful or not. Pre-exposure to some of the topics and the basics of running simple procedures has helped with my classes.”

Lighthouse’s mentorship style gives students space to grow while providing guidance when it matters most. Her background in cardiovascular research shapes the lab’s focus and offers undergraduates exposure to complex, medically relevant questions. Lighthouse previously studied cardiac fibroblasts, cells that play an important role in how the heart responds to stress. That work eventually led her to explore SGLT2 inhibitors, a class of medications originally developed to treat diabetes but later found to offer benefits for heart health as well.

To investigate these effects, Lighthouse uses an unexpected but powerful research model: Caenorhabditis elegans, commonly known as C. elegans. The organism is a tiny, translucent worm measuring about one millimeter in length. Despite its size, it allows researchers to observe how stress and disease affect an entire living system.

Smith has learned to work directly with C. elegans, using the organism to model metabolic changes linked to diabetes and heart disease. The research helps explain why SGLT2 inhibitors may protect cardiac health, even though the drugs were not originally designed for that purpose.

“Even though worms and humans look and function very differently, there are still some basic physiological mechanisms that occur the same way in both species,” Lighthouse said.

For Smith, working with C. elegans has reinforced an important lesson: meaningful medical research often begins with simple organisms and careful observation. The experience has helped her connect biology, chemistry, and physiology in ways that lectures alone cannot provide.

Lighthouse strongly believes in the value of undergraduate research. She notes that students who engage in research develop stronger critical thinking and problem-solving skills, learn how to collaborate effectively, and become more comfortable navigating failure. Those experiences mirror the challenges scientists and physicians face throughout their careers.

Her own journey began as an undergraduate researcher, an experience that helped her discover a future in science. Now, as a faculty mentor, she aims to show students that science is not static or predictable, but constantly evolving.

“I think getting involved in undergraduate research is really valuable to show students how diverse and dynamic science is, and that scientists are innovating, pushing boundaries, and challenging themselves on a daily basis to improve our understanding of how our world works,” Lighthouse said.

National organizations echo that perspective. According to the Council on Undergraduate Research, hands-on learning and mentorship play a major role in student success. By working closely with faculty and participating in real research, students gain skills that are highly valued by graduate schools and employers alike.

Under Lighthouse’s guidance, Smith is learning how to ask clear research questions, analyze data, and present findings to others. She is also gaining experience communicating science through presentations at RIT’s annual Undergraduate Research Symposium, where students share their work with the campus community.

“Just having research experience alone will help me in the medical school application process, but I think it’s important to be well rounded,” Smith said. “We also read and summarize papers and apply them to what we’re doing. It’s good experience to have.”

As Smith continues her undergraduate studies, her time in the lab remains a cornerstone of her preparation for medical school. Through mentorship and research, she is learning not just what to study, but how to think—an essential skill for any future physician.

-

Local News12 months ago

Local News12 months agoNew ALDI store close to Rochester to begin construction in late 2025 or early 2026

-

Local News11 months ago

Local News11 months agoRochester Lilac Festival announces exciting 127th edition headliners

-

Local News9 months ago

Local News9 months agoCounty Executive Adam Bello and members of the county legislature celebrate exceptional young leaders and advocates at the 2025 Monroe County Youth Awards

-

Local News9 months ago

Local News9 months agoThe 2025 Public Market Food Truck Rodeo series will begin this Wednesday with live music by the Royal Bromleys