Local News

New study shows that adjusting the brain’s immune response could reduce early damage linked to Alzheimer’s disease

Rochester, New York – In a major step forward in understanding Alzheimer’s disease, scientists have found that adjusting how the brain’s immune system reacts to damage could help slow or even prevent the illness from worsening. The new research, which zeroes in on a brain chemical called norepinephrine, reveals that supporting the brain’s natural defenses early in the disease may reduce inflammation and protect brain cells before serious damage sets in.

This study, led by researchers from the Del Monte Institute for Neuroscience at the University of Rochester, focused on the complex interplay between brain chemicals and immune cells. The findings could eventually lead to more targeted, earlier treatments for Alzheimer’s—especially ones that take into account each patient’s unique biology.

“Norepinephrine is a major signaling factor in the brain and affects almost every cell type. In the context of neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease, it has been shown to be anti-inflammatory,” said Ania Majewska, PhD, senior author of the study. “In this study, we describe how enhancing norepinephrine’s action on microglia can mitigate early inflammatory changes and neuronal injury in Alzheimer’s models.”

The results, published in the journal Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, show that norepinephrine—a chemical that helps regulate alertness, stress, and inflammation—plays a far more powerful role than previously understood in protecting the brain against Alzheimer’s-related damage. This protection comes through its influence on microglia, specialized immune cells that serve as the brain’s first line of defense.

Understanding the Immune Connection

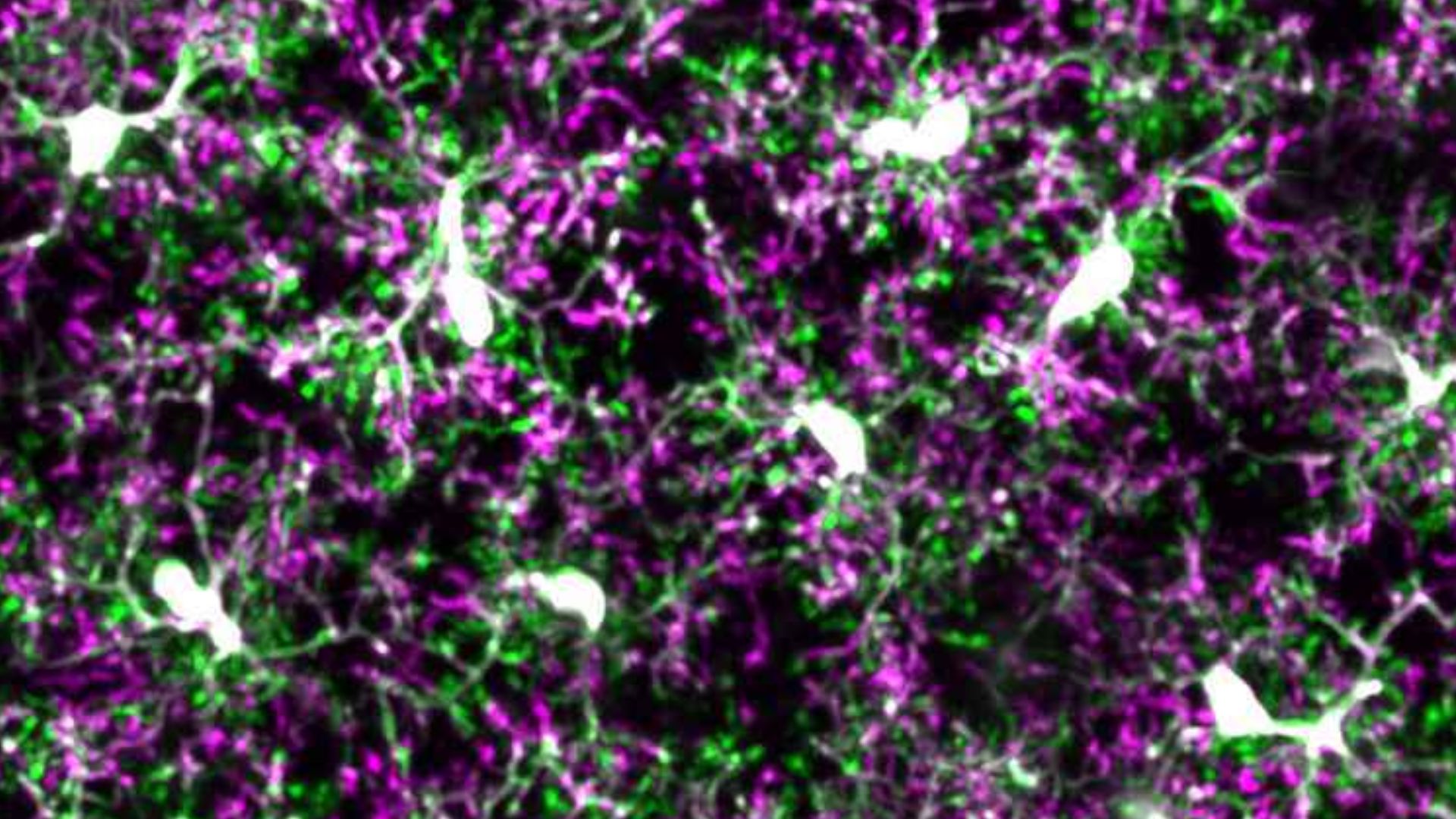

In healthy brains, microglia act like internal custodians. They constantly monitor their surroundings, cleaning up waste and responding to potential threats. But in Alzheimer’s disease, especially as amyloid plaques begin to form, microglia become overactive and inflamed—ironically causing more harm than good.

This study showed that a key reason for this harmful shift may be due to a loss of sensitivity to norepinephrine. Microglia normally respond to norepinephrine through a specific receptor known as β2AR. Think of it like a switch that tells microglia to tone down their immune response. In aging brains and in those affected by Alzheimer’s, this switch becomes weaker, especially near plaque-heavy areas.

As microglia lose their β2AR receptors, they also lose their ability to self-regulate. The result is more inflammation, more plaque accumulation, and greater damage to the surrounding brain cells. But here’s the exciting part: when scientists restored or stimulated the β2AR receptor in mice, they saw less inflammation and fewer signs of damage.

A New Perspective on Treatment

While many Alzheimer’s therapies in the past have aimed at reducing plaque directly, this research suggests another route—helping the brain manage its own immune response better, especially in the early stages of the disease.

“In this study, we describe how enhancing norepinephrine’s action on microglia can mitigate early inflammatory changes and neuronal injury in Alzheimer’s models,” said Majewska.

The research also found that blocking the β2AR receptor or genetically removing it made things worse. Without that calming signal, microglia became hyperactive, driving up brain inflammation and damaging neurons even more.

These discoveries could dramatically shift how scientists and doctors approach Alzheimer’s treatment in the future. Instead of waiting until there is widespread damage, a strategy that targets microglia early on could slow the disease before major memory or cognitive loss appears.

Even more interesting is the personalized element of the findings. The effectiveness of receptor stimulation varied depending on when it was introduced and the sex of the animal, suggesting that personalized treatment strategies might be necessary for human patients.

Future Possibilities and Drug Development

These new insights could lead to a wave of treatments focused on the β2AR receptor or on stabilizing norepinephrine signaling in the brain. By keeping microglia in check and reducing inflammation, such drugs could offer a preventative approach to a disease that has long been considered unstoppable once it starts.

However, much work remains. This study was conducted in mice, and researchers are careful to note that human brains are more complex. Still, the study’s implications are encouraging. With continued research, medications that work with the body’s natural brain chemicals to control immune responses may become a key piece in Alzheimer’s prevention and care.

“In many cases, treatments are only tested or administered when the disease is already in full swing,” said Majewska. “But this study hints at a window of opportunity much earlier, when intervention might actually slow or stop the progression.”

The research team also included Linh Le, PhD, a graduate student working in both collaborating labs, as well as co-authors Alexis Feidler, Lia Calcines Rodriguez, MacKenna Cealie, Elizabeth Plunk, Herman Li, Kallam Kara-Pabani, Cassandra Lamantia, and Kerry O’Banion. Funding for the study came from several key sources, including the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, the Alzheimer’s Association, the National Institute of General Medical Sciences, and the University of Rochester.

As Alzheimer’s continues to affect millions worldwide, breakthroughs like this offer renewed hope. By looking beyond the usual suspects—plaques and tangles—and turning attention to the immune system’s role in the brain, researchers may be on the verge of a new era in treating and possibly preventing this devastating disease.

-

Local News12 months ago

Local News12 months agoNew ALDI store close to Rochester to begin construction in late 2025 or early 2026

-

Local News12 months ago

Local News12 months agoRochester Lilac Festival announces exciting 127th edition headliners

-

Local News10 months ago

Local News10 months agoCounty Executive Adam Bello and members of the county legislature celebrate exceptional young leaders and advocates at the 2025 Monroe County Youth Awards

-

Local News10 months ago

Local News10 months agoThe 2025 Public Market Food Truck Rodeo series will begin this Wednesday with live music by the Royal Bromleys