Local News

RIT researchers develop a groundbreaking new recipe that could transform 3D bioprinting of stronger and more realistic human-like tissues

Rochester, New York – A team of researchers at Rochester Institute of Technology has taken a significant step forward in the evolving world of 3D bioprinting, developing what they describe as a new “recipe” that could help create stronger, more realistic human-like tissues. Their work tackles one of the most stubborn challenges in tissue engineering—finding a material that can safely support living cells while still being strong enough to form stable structures during the printing process.

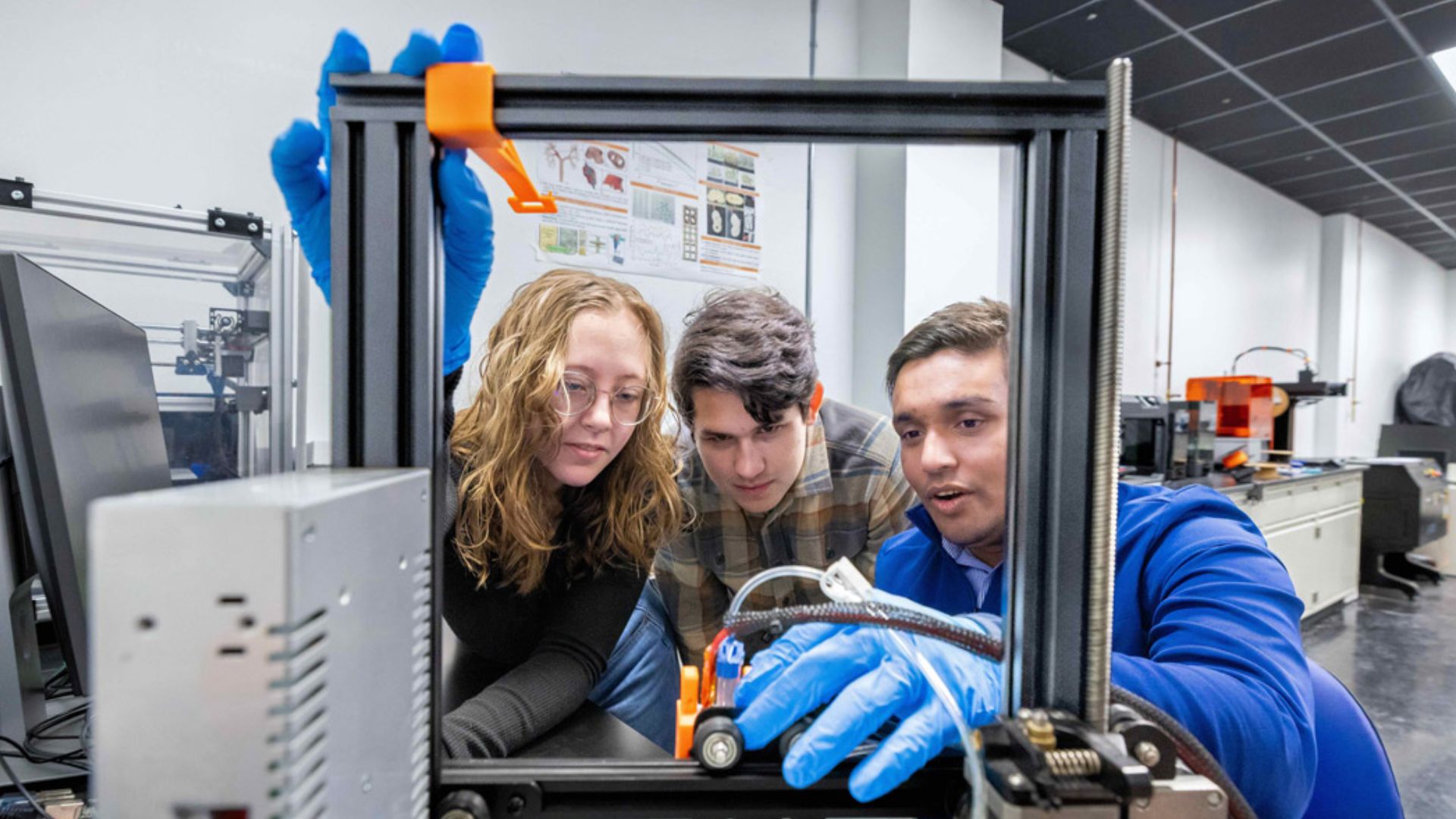

The research, led by professors Ahasan Habib and Christopher Lewis, brings together faculty expertise and student innovation across multiple engineering disciplines. The team included undergraduate researchers Riley Rohauer and Perrin Woods, whose hands-on contributions helped transform complex scientific concepts into practical laboratory solutions.

At the center of their breakthrough is a carefully engineered hydrogel—a soft, water-rich material designed to act as a supportive environment for living cells. Scientists have long struggled to balance two competing needs: the gel must be gentle enough to protect delicate cells while also strong enough to hold its shape as it is printed layer by layer.

“We tried to design and prepare a dual cross-linkable material. We wanted to make sure we can control the various properties of the final 3D printed parts,” said Habib, who is an expert in additive manufacturing, specifically toward functional bio-tissue scaffolds. “We needed to find a ‘sweet spot’ where we can extrude the matter to get a defined 3D structure, because we are preparing bioink—biomaterials plus cells together —and we wanted to be sure that we are not damaging the cells in the process.”

Finding that “sweet spot” required extensive experimentation. The team tested multiple combinations of natural and synthetic polymers, carefully studying how each mixture behaved under pressure, heat, and chemical reactions. Ultimately, they succeeded in creating a formula that allowed printed structures to remain soft and flexible without collapsing during production.

Equally important was ensuring that the cells embedded within the material remained alive and functional throughout the process. This meant closely examining the physical and chemical properties of the hydrogel, including how it flows through tiny nozzles and how it reacts to stress.

“Cells in the hydrogel are moving through a microscale tube, a nozzle,” said Habib “Our big goal is a dual crosslinking system. If we change the recipe of the material, how will it be impacted rheologically, physically, chemically and mechanically to eventually do a type of dual printing of bioinks?”

Rheology—the study of how materials behave under force—played a key role in the project. In bioprinting, even small changes in pressure or movement can damage living cells or distort the final structure. By understanding these forces, the researchers were able to fine-tune their hydrogel so it could flow smoothly through a printer while still solidifying into stable shapes.

To complement the new material, the team also developed a custom-built bioprinter capable of performing a complex process known as dual crosslinking. This involves strengthening the hydrogel in two stages, allowing it to maintain both flexibility and structural integrity.

Woods, a senior engineering student who built the device, designed it to use ultraviolet light during the printing process. The light triggers a chemical reaction that transforms the liquid bioink into a stable gel almost instantly, eliminating the need for separate curing steps after printing.

One of the major goals of the device was to ensure that the biomaterial solidified while it was still being deposited. Traditionally, curing and printing occur in separate stages, which can lead to distortions or inconsistencies. By combining both processes into a single step, the new system allows for more precise and reliable tissue scaffolds.

“You can 3D-print objects and tissues with a typical 3D printer, but the material may be wrong. Or you can get the right material, and you may not get the right geometries. That is where our lab and our materials come in,” said Woods. “We are able to say, bio-printing in a hydrogel can get you close to the tissue engineering solutions you need.”

The project also served as a powerful learning experience for the students involved. Rohauer, a biomedical engineering student, described how the research challenged her to master new laboratory techniques while contributing to real scientific discovery.

“It was a great learning curve for me,” said Rohauer, a third-year biomedical engineering student from Guilderland, N.Y. “As I was learning to create and characterize material. I was also learning scientific techniques up front.

“And as I became more confident, the data got better. Then Perrin came in and the print test corroborated what we were seeing with the chemical structure. It behaved the same way in ‘real life’ as it did on the machine. It was a really cool experience for me to see it move from one application to another.”

Woods echoed that perspective, emphasizing the broader significance of the work.

“We found the initiator, the chemical in the material that is going to photo-cross link. Dr. Habib has a really great vision for where this technology is going, both on the material and hardware sides. Tissue engineering is still preliminary, and these are the building blocks of a field.”

Researchers say the implications of their work extend beyond a single material or printer design. The hydrogel characteristics they identified could help scientists create tissues that closely resemble human organs such as the brain, kidneys, and heart. These lab-grown tissues could eventually play a role in medical research, drug testing, and regenerative medicine.

The findings were published in the January issue of the Journal of Functional Biomaterials, highlighting the collaborative nature of the project. In addition to Habib, Lewis, Rohauer, and Woods, the research team included graduate and undergraduate contributors from multiple engineering programs, as well as a visiting research assistant who participated during the summer of 2025.

For Habib and his colleagues, the work represents an important step in solving one of the central puzzles of tissue engineering—how to combine living cells with supportive materials in a way that preserves both biological function and structural strength.

While fully functional lab-grown organs remain a distant goal, advances like this bring researchers closer to that future. By refining both the “recipe” for bioinks and the tools used to print them, the team has opened new possibilities for creating human-like tissues that are not only realistic in form but also resilient enough to be studied, tested, and potentially used in medical treatments.

-

Local News1 year ago

Local News1 year agoNew ALDI store close to Rochester to begin construction in late 2025 or early 2026

-

Local News12 months ago

Local News12 months agoRochester Lilac Festival announces exciting 127th edition headliners

-

Local News10 months ago

Local News10 months agoCounty Executive Adam Bello and members of the county legislature celebrate exceptional young leaders and advocates at the 2025 Monroe County Youth Awards

-

Local News10 months ago

Local News10 months agoThe 2025 Public Market Food Truck Rodeo series will begin this Wednesday with live music by the Royal Bromleys