Local News

RIT researchers develop a simpler and more efficient method for predicting chaotic systems

Rochester, New York – That vivid image, first used by mathematician Edward Lorenz in the 1960s, became the symbol of chaos theory — the idea that tiny shifts at the start of a system can explode into massive, unpredictable consequences. For decades, scientists have wrestled with that unsettling truth. If small changes can spiral into chaos, how can anyone hope to predict what comes next?

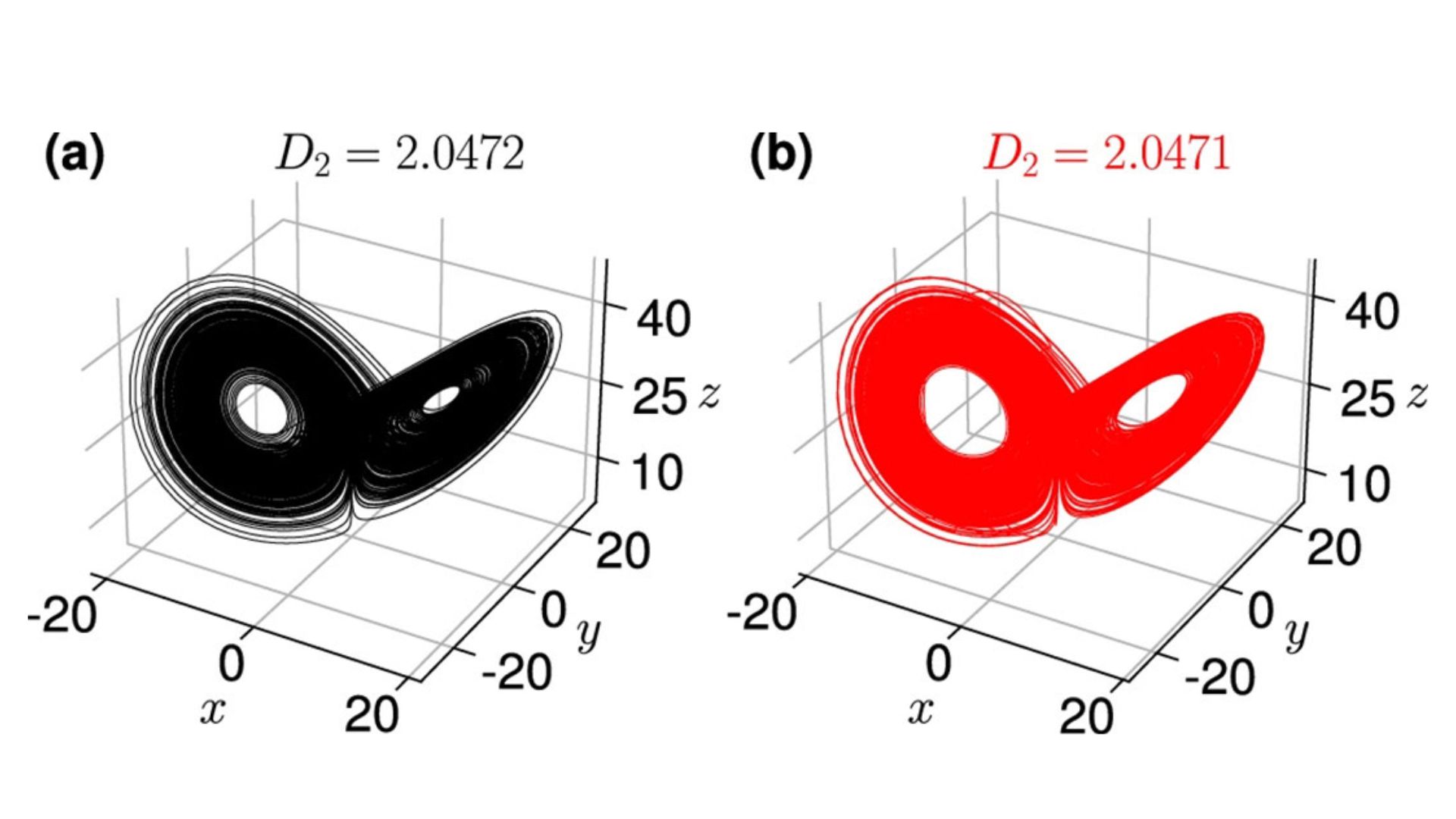

Now, a research team from Rochester Institute of Technology believes they have taken an important step forward. They have developed a new method for forecasting chaotic behavior using less data, fewer parameters, and a format designed to be easier for researchers to use and understand.

The work was led by Adam Giammarese ’21 BS/MS (applied mathematics), ’25 Ph.D. (mathematical modeling), and Kamal Rana ’23 Ph.D. (imaging science), alongside Nishant Malik, associate professor in RIT’s School of Mathematics and Statistics. Their findings were published in Nature Scientific Reports, marking a significant milestone for the team.

Chaos theory centers on a simple but daunting principle: systems that appear stable can become wildly unpredictable if their initial conditions shift even slightly. This concept plays a critical role in weather forecasting and climate science, where small measurement differences can alter long-term predictions. It also reaches into fields like health and finance, where complex systems evolve in ways that are difficult to anticipate.

“Forecasting chaos is an impossible problem,” said Giammarese. “But if you can develop something that’s easy to use and can still forecast to a certain level to try to match other results out there, then that would be incredibly valuable. That’s what our paper was focused on.”

The idea behind the project traces back to 2019, when Giammarese and Rana were students in Malik’s dynamical systems class. At the time, researchers were heavily discussing neural network-based algorithms for predicting chaotic systems. Neural networks — powerful tools inspired by the structure of the human brain — can uncover patterns in complex data. But they often require large datasets, extensive computational power, and significant expertise to interpret.

Rana, whose doctoral research focused on decision trees — a more traditional form of machine learning — saw an opportunity. Decision trees are structured like branching diagrams, breaking down decisions into simple steps. Compared to neural networks, they are far less complicated and use fewer adjustable parameters.

The idea was straightforward but bold: apply tree-based learning methods to the deeply complex problem of chaos prediction.

As Rana shifted his focus to other research, Giammarese continued developing the project. The team explored whether these simpler algorithms could stand up to a problem widely considered one of mathematics’ toughest challenges.

“Anyone, whether they have expertise in chaos theory or whether they have expertise in machine learning, can use this really simple, straightforward algorithm,” explained Malik. “Neural-network-based methods are powerful and offer many advantages, but they’re often hard to interpret. Classical methods like decision trees are easier to understand, more transparent, and simpler to use.”

That simplicity is not just a matter of convenience. More complex models demand large volumes of data and repeated computational runs, placing strain on machine learning infrastructure and data centers. In fields such as weather and climate science, datasets are often limited in size. Under those conditions, classical algorithms like decision trees can perform effectively without the heavy resource requirements of neural networks.

The researchers describe their guiding principle as accessibility. They aimed to close a gap in the field — to connect classical, well-understood tools with one of science’s most complicated problems.

“The whole ethos of this research project is to make this as user friendly as possible,” said Giammarese. “I think we were trying to hit the research gap of bridging a classical method and a really difficult problem where we can use simple algorithms to solve really complex problems.”

In addition to Giammarese, Rana, and Malik, the late Erik Bollt, W. Jon Harrington Professor of Mathematics at Clarkson University, contributed as a co-author to the study.

The team’s approach does not claim to eliminate uncertainty — chaos, by its nature, resists complete control. But by reducing the complexity of the tools required to analyze it, the researchers have opened the door to broader use and experimentation. In a field long defined by unpredictability, even modest gains in clarity can carry far-reaching impact.

From butterflies to tornadoes, the mathematics of chaos remains as humbling as ever. Yet with simpler tools and clearer methods, scientists may now be a step closer to understanding how small beginnings shape enormous outcomes.

-

Local News12 months ago

Local News12 months agoNew ALDI store close to Rochester to begin construction in late 2025 or early 2026

-

Local News12 months ago

Local News12 months agoRochester Lilac Festival announces exciting 127th edition headliners

-

Local News10 months ago

Local News10 months agoCounty Executive Adam Bello and members of the county legislature celebrate exceptional young leaders and advocates at the 2025 Monroe County Youth Awards

-

Local News10 months ago

Local News10 months agoThe 2025 Public Market Food Truck Rodeo series will begin this Wednesday with live music by the Royal Bromleys